This Sorry Spacesuit 024- But In Other Respects It Is Light: The Legacy of Jay Defeo

“I believe the only real moments of happiness and a feeling of aliveness and completeness occur when I swing a brush. I don’t think I can do without it.”

-In a letter to her mother in 1952.

In 1988, Jay Defeo knew she had lung cancer.

She had found a wounded dove in her basement, something her dogs must have got a hold of. She put it in a shoe box and rushed it to a vet, but it was too late. She was affected by the death and the image of the still bird in the box- it’s glassy black eye pointing back at her, stuck.

Some would say that the style she was using at the time seemed a far cry from the works she created in the 70’s, when she had returned to art-making after the ordeal of The Rose. She was using the palette of her earlier career; warm light muds pushed together with strong black and whites. She spent most of her time in the greys, shoving around highs and lows to blend out soft edges- building up forms with the black and white then knocking some of them down again. Sculpting areas of interest and focus with paint.

Jay Defeo was an artist of the beat generation. Her artwork was hanging on the walls in the room when Allen Ginsberg read “Howl” in public for the first time. She was likely there to hear it, as her husband Wally Hedrick was a founding member of the art space in which Ginsberg read it. Defeo and Hedrick kept a little apartment on Fillmore street in San Francisco which became a hub for poets, musicians and painters in the burgeoning beatnik scene.

Before that she spent time in Europe. She visited Lascaux and ancient cathedrals. She made over 200 paintings during a 3-month stay in Florence. When she returned, she taught art classes for kids until she was fired for being convicted of shoplifting two cans of paint.

Her and Wally struggled to make ends meet. She made jewelry, took odd jobs and kept painting.

When Jay Defeo died at the age of 60, her most important work The Rose– a piece she made during her time in that little apartment on Fillmore- had been seen sealed up behind a wall for over a decade. And it would take close to another decade before anyone would see it.

She began The Rose in 1958. And she was still working on it in 1966 when she was evicted. Some of her friends said being evicted was a blessing, it’s what finally took the work out of her hands. The painting had become her obsession.

She worked and reworked the surface. She scraped it down and built it back up. She used only paint, occasionally mixing in powdered mica. She would finish a section one night, only to wake up the next morning and find that the heavy paint had slid down with the night’s gravity. So she would scrape it off and start over.

Six months in, she decided that the composition should be centered, and it took friends a whole day to cut it away from it’s backing and place it on a new, stronger frame. They wedged the canvas into the full-length bay window of the little apartment, and she worked by the light of the little windows on each side of the painting.

Her friend and filmmaker Bruce Conner later noted that the apartment “…had no electricity; when the sun came up, the room was illuminated, she worked on the painting. When the light went away, she left the room. The room was like a temple.”

It went through phases: geometric, crystalline, organic, light, dark. She burrowed in sticks to help support it and extend the design, then she thought better of it and took some of them out. She hacked at the painting with a knife, cutting shapes into it, and deep radiating lines.

It went through whole eras of art history with her. It moved towards curves and she carved intricate designs into it’s surface, a time she called it’s Baroque Period.

The Baroque Period proved too flamboyant for her and she moved back towards a classical design, straightening the lines and building up more paint. In some areas it grew to 8 inches thick.

At the time of her eviction, the 7.5′ x 11′ painting weighed over 2,300 pounds and had to be cut out of the apartment like a tumor. A crew had to remove part of a wall so that it could be eased out of a window hole and a forklift could lower it to the street. Her friend Bruce Conner was there to document the process, cutting a short film to “Sketches of Spain” by Miles Davis. In the film Jay Defeo wears black and prostrates herself across the painting when it’s finally laid on the apartment floor. Later, she sullenly sits off to the side, watching the workmen from the third floor fire escape.

Defeo quit making art for 4 years after The Rose was removed.

The painting went to two shows and after that, it was installed in a meeting room of the San Francisco Art Institute.

A few years later it was determined that it was deteriorating- sagging under its own weight- so it was covered over with wax and plaster in a haphazard attempt to preserve it. And a few years after that, the institute got tired of seeing the mess and put a wall up in front of it.

There it would sit, covered over with plaster behind a wall for decades, becoming a myth until 1996 when the Whitney Museum started collecting work for a retrospective on beat culture and had the notion to excavate it. They pulled down the wall, and built a new structure to properly support the painting’s weight. With all the reverence of anthropologists, they lovingly removed the plaster and wax and painstakingly cleaned it. And when it was ready, they put it in a small black space with a diffused light on each side, mimicking the little bay windows of the apartment on Fillmore Street.

The whole piece now has the feeling of a monument. Despite the relentless commitment to the radiating composition, I don’t feel like it’s bursting out from the center. Instead it crumbles from the top, erupting from caked earth. My eyes aren’t drawn to the center as I would assume, but instead they tend to rest on the lower third, in the high contrast area where she put the boldest cuts- deepest relief- and the black she left showing, like a vein of ore. She shows her mastery of the effects of contrast.

The powdered mica that she mixed into some of the paint layers has a reflective quality. It shimmers, it glows, it radiates. It’s called The Rose, yet it fans out like a dove.

It’s 11-feet tall and weighs over 1 ton, and yet it looks light. Suspended or lifting.

Some people say that this ponderous work was a symbol for the culture that bore it. And that being evicted from it’s little manger on Filmore Street- and later covered over and neglected on the wall of an art institute- was a coffin-nail for the once vibrant beat generation. In the same way that the Rolling Stones’ concert at Altamont heralded the end of the hippie era. Both well-intentioned acts gone awry, and beyond anyone’s control.

As I said, when she died in 1989, no one cared for the work. 8 years of her life walled up and hidden away. And after her death the painting became a ghost, a mysterious and mythic work from an obsessive who said plainly to people that she separated her life into 2 parts: the time before The Rose, and the time after.

She was changed by this piece, inside and out. The lead paint and turpentine that she breathed in during those eight years working in that little alcove of her apartment gave her a deteriorating gum disease which later made her teeth fall out.

But while The Rose may be Defeo’s largest work, it isn’t the biggest painting ever made. She isn’t the most eccentric artist we’ve known. In interviews she is coherent and shrewd, very clear about her time spent making this piece and each phase of its development. She wasn’t whisked away by the experience- where fate moved her hand for 8 years- like we assume when hearing about her obsessive dedication.

Taken as a single work The Rose, while impressive, is a small, quirky and compelling footnote in a slightly larger, quirky and compelling footnote of American cultural history.

So why is it a big deal?

This painting is from 1988. The year of her cancer diagnosis and heading into the last year of her life. It’s the memory of that dove she put in a shoe box and couldn’t save.

And It’s 16″ x 20″. Inches, not feet.

These paintings are studies of the dental bridge that she was given when her teeth fell out. They were the first things that she made when she finally got over her obsession with The Rose.

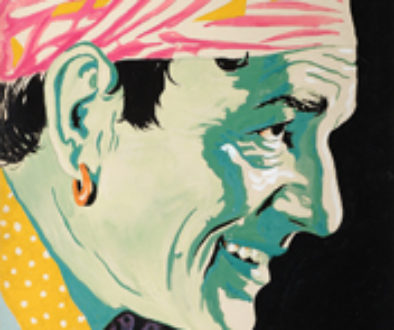

Origins, from 1956- 2 years before The Rose.

The Verónica, from 1957.

Persephone, from that same year.

Verdict #1, from 1982.

And I had another dozen that I would have put alongside these. They show her incredible versatility and intelligence.

Jay Defeo may have been a part of the beat generation, but she is also part of a larger, more complex community. Creators that are unflinching in their dedication and committed to turning over every stone they can find. Artists who decide for themselves when it’s time to stop.

The Rose by itself isn’t what makes Jay Defeo one of my favorite artists. I’ll be honest, when I first came across this story, I didn’t think much of The Rose. It seemed like a lot of hoopla over a big (and admittedly very pretty) thing. A painting whose purpose was it’s size, and while that’s respectable, it’s also not that unique and didn’t jump the rails in its intention. It moved through some pretty country, to be sure. But really it was just a train that showed up on time.

But when I looked for her other work and saw The Dove #1 and I put them both under one hand, a silhouette emerged of an artist with incredible versatility and strength. Then I found her collage work. Her work with ink and photocopiers. Her early work in Florence, her jewelry, her drawings, her bold choices, her humor, her dedication to craft, her aesthetic. I realized that I had completely misunderstood The Rose.

In 1959, she was invited to be in a show in New York. The “Sixteen Americans” show at MOMA was groundbreaking and included a roster of names that would come to dominate the art world: Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson and Frank Stella as well as Wally Hedricks. They wanted to include The Rose but Jay Defeo said it wasn’t done and she didn’t know when it would be and she wasn’t going to rush it.

So they ran a picture of it in the catalogue. They heralded it as a great work and this was just a few months into it. The composition hadn’t even been centered yet.

I wonder how they felt about the 7 years of changes it went through afterwards. Whether they understood that it was called The Rose for the way it blossomed.

I’m pretty sure that Jay didn’t care. She was busy making it right.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this essay. If you’d like to receive more stories like this, please sign up for the This Sorry Spacesuit newsletter below. Once a month or so you’ll get an email with a story or discussion on art, music, history etc.- Something like what you’ve read here. And when you sign up, you’ll get access to the archive- over 30 more posts, stories and essays like this.

This isn’t a marketing platform, just letters in a digital bottle tossed into the glimmering sea of content, that hopefully will spark conversations which are more than 140 characters long. There is NO sales-pitching or spam.